CAMES: The Future of Medical Education and Simulation with Lars Konge

In this interview, Lars Konge, certified cardiothoracic surgeon and founder of the Copenhagen Academy for Medical Education and Simulation (CAMES), discusses the success of CAMES, which is known as the “Silicon Valley” of simulation. He also shares his insights on the shift in the acceptance of VR simulation for training and assessment in surgical education, as well as the group’s focus on research in higher levels of the Kirkpatrick Pyramid. Konge also shares findings from their studies on the efficacy of VR simulation training, patient outcomes, and cost savings.

Hi Lars, can you give us some background on what you do and the Copenhagen Academy for Medical Education and Simulation (CAMES)?

I am a certified cardiothoracic surgeon and when I was specializing, 10 years ago, I did a PhD on how to use simulators in training and assessment. Afterwards, I was asked to start a technical skills center that later became known as CAMES. We started with just one room and now have over 27 rooms dedicated to simulation-based training.

In May we are moving into a new 3000m2 building opposite the main hospital in Copenhagen, with more than 4,000 medical students. We will have our own research unit, a regional research support unit, and the innovation unit, creating a Silicon Valley for simulation.

And what will the group be focusing on over the next few years?

We are bringing in a pilot and health economists and move our research into the ‘real world’ and look at the higher levels of the Kirkpatrick Pyramid.

The first level of the pyramid is where you measure a trainee’s satisfaction. The next level, you measure the actual training in the simulation center. The third, you go into the real world and see if trainees are performing better and if their skills have transferred into the OR.

In the fourth layer, we look at the efficacy on patients, to see how we can minimize or reduce complications and even reduce mortality. And then in the final layer we will look at the return on investment, to show what we’re doing in the simulation center doesn’t cost money, it saves us money. And this is the layer we want to do more research on.

So, there has been a real shift in using VR simulation for training surgeons?

Definitely. When I got my first VR simulator, in 2006, it was considered to be a toy. But over the last few years, with VR training and assessment based on evidence, we really feel a shift. From a toy used in an unstructured way to structured training programs that are now becoming increasingly mandatory for all trainees.

For example, in Denmark, a month ago, it became mandatory for all trainees in orthopedic surgery to use a simulator in their training and pass a simulation test. So, that’s one of the biggest changes, it has now become acceptable. The next step on the journey is that it becomes mandatory for all surgical training.

This study shows that every time a trainee practices on the simulator, long-term, you’ll end up saving several thousands of dollars.

You’ve been measuring the effects of VR training in terms of patient outcomes and costs?

It is more than 10 years ago since we published in the British Medical Journal, the much-quoted study showing that Gynecologists who practice on a VR laparoscopic simulator would improve 50% and get better and quicker performance after simulation-based training.

Now we have moved away from that kind of research as we have more than a thousand studies showing that it’s better to practice than not to practice, the third layer of Kirkpatrick’s Pyramid. Now we are moving up to the fourth layer and measuring efficacy on patients.

We have just finished a project for endobronchial ultrasound. This study shows that every time a trainee practices on the simulator, long-term, you’ll end up saving several thousands of dollars

Is that just from the time saved during the procedure?

We have evidence showing that the procedures are done quicker, with fewer complications, and health economists can work out a cost saving. That’s obvious. The surgical theater is a very expensive training ground; you need a supervisor, an anesthesiologist, at least two nurses and then the patient.

Practicing on patients has been shown to be expensive, even supervised practice on patients results in more complications and higher costs. And that has been shown in large studies with more than 100,000 patients. Also, from an ethical viewpoint, I find it undefendable to practice on patients when you have a good alternative.

When residents are training on patients, they usually perform only simple procedures and not more complicated ones.

We’ve done a lot of research in VATS, Video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery, a complicated and dangerous procedure. One of the first studies we published was my own learning curve more than 10 years ago.

I spent 12 months learning how to do VATS. I was totally dedicated, working close to 3000 hours. In one year, I managed to have 29 training operations. So, compare that to now.

With a VATS simulator, we have shown that the learning curve can be hugely improved. By doing the first 29 operations on a simulator it will take you 12 days, not 12 months. That’s the truth about traditional apprenticeship learning.

You also need to practice in a more structured and efficient way. I heard about an interesting case 2-3 years ago, where the senior doctors were so busy that they didn’t have time to supervise their trainees, so they asked them, “Are you able to do this operation by yourself?” If the trainee said “No, I would like to be supervised” the supervisor would do the procedure instead of supervising. It takes like twice as long time to supervise a trainee, compared to doing it yourself.

And then the trainees learned to say “Yes I’ll do it.”. They performed the operation as well as they could and, of course, when there were problems they asked for supervision. That’s a very unsafe training environment for the patients. After this, the department recruited a simulation minded head of education and a lot of the initial training is now in the simulation center.

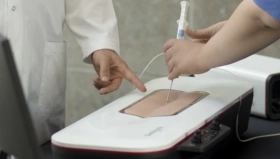

Yes, learn the initial fundamental skills on a simulator rather than a patient.

Every surgeon would agree that it can be frustrating to supervise a complete novice in the OR. You’ll see a trainee’s hand moving right on his instrument but moving it left due to the fulcrum effect. It’s difficult to learn this and it should not be learned on patients. It’s even stressful for the trainee. It’s not fun to train on patients.