Surgical Science and The Greater Stockholm Veterinary Care Foundation have been collaborating on a project to design and build virtual reality simulators for training veterinarians to perform canine laparoscopic surgery (female dog spay procedure). Odd Viking Höglund, DVM, is the medical adviser appointed by the Foundation and he recently introduced the new simulation in his teaching at the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences in Uppsala, Sweden. We caught up with Odd to ask him about how the project has developed – and the reaction of his students to this breakthrough technology.

Tell us a bit about how you got involved in the project?

Odd Viking Höglund: I’ve attended medical surgery conferences – both human and veterinary – for many years, so I was already aware of Surgical Science’s simulators for various surgical procedures. For me, it has been fascinating to see how the sophistication of these simulators has developed as robotics and virtual reality technology has improved. I had often wondered about the potential for bringing these techniques into the work I do as a trainer of veterinary students. Coincidentally, a colleague working for The Greater Stockholm Veterinary Care Foundation was thinking the same thing, and the Foundation agreed to fund this initial collaboration to design and create the first simulator dedicated to canine spaying. It has been extremely exciting to see the theory become a reality!

What are some of the challenges in training veterinary students that the simulators are helping to solve?

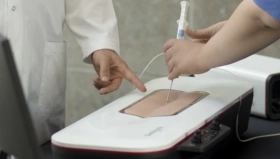

Odd Viking Höglund: Prior to performing operations on live animals, students obviously do a lot of theory. We prepare them for surgery by teaching them basic suturing skills, and making sure they are familiar with surgical equipment. They are then presented with dummies and cadavers, where they learn how to open the abdomen and perform the spaying procedure.

These simulators will revolutionize the training process, because they provide limitless opportunity for practice. One of the biggest benefits is that, as well as building a student’s skill and dexterity, the simulators give them confidence. The first time you are presented with a live animal, it can be extremely nerve-wracking. This is a fantastic way to reduce anxiety and improve the mental health of students and inexperienced practitioners by ensuring they feel comfortable in a surgical environment.

What has been the process for developing existing human anatomy surgery simulation into veterinary programs?

Odd Viking Höglund: In some ways, the existing technology developed by Surgical Science for human procedures was already viable for veterinary training. There are certain simulations that already exist for training basic surgical skills, as well as specialised procedures, such as removing the gallbladder or appendix. All of these give our students the potential to develop their surgical skills. But for the laparoscopic spay procedure, we needed to build a completely new virtual environment that accurately represented canine anatomy.

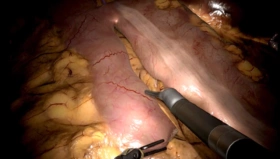

To do this, we worked closely with the team at Surgical Science, providing them with images and videos of live canine surgeries. That allowed them to design the software and create near-perfect representations of the canine anatomy in the simulation environment. We also invited the programmers to observe the work we do, both with live surgical procedures and with cadavers. This gave them the chance to not only see the process, but feel it too. Uniquely, Surgical Science’s simulators are tactile, so users can feel resistance of the tissue on the instruments within the simulation, which makes the experience as immersive and realistic as possible.

So far, the program has focused on canine laparoscopy. What are some of the benefits of this type of surgery for dogs?

Odd Viking Höglund: There have been numerous studies that show animals recover more quickly from laparoscopic (or ‘keyhole’) surgery, a procedure that minimizes the dog’s stress reaction to the operation, referred to as ’surgical stress’. Our students have never really had the chance to practice these types of procedures before. Working with cadavers is limited to open surgery – and, of course, they can only perform the operation once each time. The laparoscopic option is less invasive, and often preferable from an animal welfare point of view. The simulators will allow students to develop their skills more quickly, and provide owners with more choice on how a neutering procedure is performed, as more vets would be trained and available to offer the laparoscopic procedure.

What has the reaction of your students been to the new simulators?

Odd Viking Höglund: The immediate feedback has been super-positive. When I first showed the simulators to my students, they were immediately hooked! One thing I hadn’t really thought about was how technology uses data to enhance the learning process. These machines measure everything: They will score your success, and provide you with scope for improvement. This ‘gamification’ of the academic experience makes it incredibly accessible and engaging.

Of course, working with cadavers will remain a vital part of training. After all, they give students the chance to see the real anatomy close up, rather than displayed on a screen. But they also present practical and ethical limitations. I see the simulators as being an invaluable tool for helping students build up their skills and experience – and, crucially, their confidence – as they prepare for a live surgical environment.