The disruptive technology of robotic-assisted surgery has enabled surgeons from many different specialties to now offer truly minimally invasive procedures to an increasing number of patients who previously were never candidates for this approach. However, this innovative technology has created unique issues in the operating rooms. One critical issue has been the effect that robotic surgery has had on communications among the OR staff and the surgical team.

The surgeon operates in a robotic console, typically remote from the patient and other team members. Communication is therefore hindered between the surgeon and his/her team. Other factors, including ambient OR noise and a darkened environment, contribute to the lack of awareness by the surgeon of what is happening in the OR environment. In addition, team members often do not know what the surgeon wants them to do in order to better help with the procedure. On top of this, traditional OR culture has caused some team members to fear speaking up if they don’t understand what is going on or, more importantly, if something seems amiss.

The aviation industry had a similar problem prior to the 1970s when the senior pilot captain oversaw the aircraft (similar to the senior surgeon being in charge of the OR care of the patient). A horrific accident occurred on the small Atlantic island of Tenerife in March 1977 when the chief pilot for Lufthansa airlines taxied his Boeing 747 aircraft full of passengers onto an active runway and was hit by another Pan AM Boeing 747 taking off. The death toll came to 583, making it the deadliest aviation accident in history. An accident investigation revealed that the primary cause of the accident was poor communication among the tower and the two aircraft. The KLM pilot thought he had been given clearance to taxi, but the copilot failed to tell him that he hadn’t. The copilot and flight engineer in the cockpit were likely aware of the abnormal situation but were afraid to speak up.

The aviation industry quickly moved to prevent accidents like this from ever happening again by instituting a process called “Crew Resource Management,” or CRM. This process required teams to train together and empowered everyone on the flight team to speak up at any time if they felt something was occurring that was abnormal or unsafe. Another safety measure that was instituted was an increased reliance on check lists for every aspect of the flight. Going through these checklists, crews utilized “Cockpit Communication.” This communication process requires that pilots repeat everything back to each other and also to the air traffic controllers to ensure that all commands and messages are heard correctly. These improvements have significantly improved aviation safety since their inception. Now it’s time to institute these safety changes into the operating room.

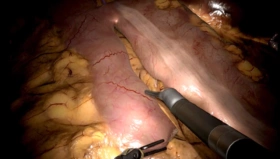

Checklists are already being used in an abbreviated fashion during the pre-procedure “Time Out,” which has become standard in most operating rooms. CRM and Cockpit Communications should be the next step of improving the OR “culture of safety.” These steps can be taught at “Team Training Courses” such as those sponsored by outside training institutions such as the Nicholson Center in Orlando, Florida, and the STAN Institute in Nancy, France. This training can involve simulation in several ways. First, didactic classes teach CRM and Cockpit Communications to all team members (Surgeons, Techs, Anesthesiologists, and Circulators), and second, simulation can be utilized to practice these new skills. A robotic surgeon can rehearse on the robot console emulator, the Mimic dV-Trainer, while connected in real time to a bedside assistant working on the laparoscopic based Mimic Xperience Team Trainer (XTT), performing the same exercises while working in the same simulation environment. Cockpit Communication skills using “read back” can be practiced during these sessions. For example, when a suture/needle is removed, the bedside assistant should state “needle out,” and the surgeon responds that he heard the message by repeating “needle out, thank you.” These dual simulation training sessions for the surgeon and assistant can be video recorded for a post-exercise discussion and review of teamwork skills and communication with a certified trainer.

Another method of simulation that is valuable for team training sessions is to video the entire OR team being confronted with a simulated emergency. This way, the team can see how they each performed their assigned roles and how their communications progressed during the exercise. These video-reviewed emergency sessions are becoming more common in most team training programs now. The future of team training will certainly involve immersive VR experiences using headsets that can incorporate one or more of the team into an actual training scenario together or remotely.

One of the keys to a successful robotic surgery program is having an experienced and professional robotic surgery team in the OR. Team training is critical to the success of these teams. This team training should not be a one-time event but should be required annually for all robotic teams. Yearly refresher courses could be offered locally by certified trainers similar to the refresher training that the aviation industry now requires for all aviators, both military and civilian. Continuing to improve the safety of our patients should be our primary goal. Utilizing joint simulation training and video review of robotic surgery teams is a proven way to reach this goal.

Author: John Lenihan Jr., MD, FACOG

Note:

Mimic Technologies is a part of Surgical Science since 2021. For more information click here.