How Measuring Learning Outcomes During Medical Training Can Help Save Lives

Copenhagen Academy for Medical Education and Simulation (CAMES) is a leading medical institution for pre- and post-graduate training in Denmark. It uses a variety of simulation tools and techniques, from traditional work on cadavers and anatomical models, to more recent innovations such as robotics, computer simulations, and virtual reality.

Lars Konge is Head of Research at CAMES and for much of his time there he has advocated for a more structured, measurable approach to training. Trainees are tested throughout their studies, and there is an evidence-based framework that ensures no-one is able to enter a ‘live’ surgical environment until they have demonstrated proficiency using simulation.

Lars Konge is Head of Research at CAMES and for much of his time there he has advocated for a more structured, measurable approach to training. Trainees are tested throughout their studies, and there is an evidence-based framework that ensures no-one is able to enter a ‘live’ surgical environment until they have demonstrated proficiency using simulation.

“Really, if you do not use testing in your training, it’s like refusing to use antibiotics to fight bacterial infections,” Lars says. “It’s old-fashioned, inefficient, and goes against all the evidence we have. Medical training simply cannot be approached using a ‘one size fits all’ model. Individuals learn at different speeds, and have vastly different levels of innate ability and confidence. You cannot simply say ‘every trainee must complete ten hours of training’ and expect them all to be ready for the operating theater.”

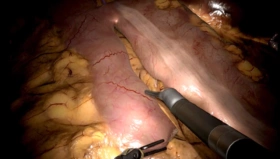

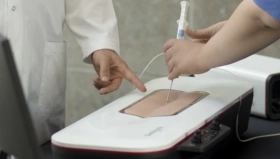

CAMES uses simulation to help trainees learn from their mistakes and practice in a controlled environment. It is safer, faster, and less stressful than having trainees observing or ‘shadowing’ surgeons working on live patients. Ultimately, it saves on costs too as it reduces the need for supervision, and results in fewer complications.

But despite the wealth of evidence supporting simulation, there are few mandatory requirements for most surgical procedures, with new medical professionals often thrust into a live environment before they have formally demonstrated their proficiency.

Lars says making wholesale changes to training programmes is a complicated process – and one that moves frustratingly slowly.

“There are three main barriers to overcome if you want to change the landscape in medical training: Tradition, budget and legislation. It is an industry where it is notoriously difficult to make significant changes to processes that have always been done ‘the old way’. And yet we know that the impact on patients is significant. A report in the British Medical Journal has shown surgical error is the third biggest cause of death after cancer and heart disease, so it is clear that improving the proficiency of new medical professionals will improve patient outcomes and ultimately save lives.”

Lars and his team have identified more than 500 procedures where clinicians believe mandatory testing should be required before trainees are authorized to perform them on patients. As yet, only a small fraction of these require formal certification.

It’s not lack of evidence, it’s lack of implementation

– Lars Konge, Head of Research at CAMES

“Our research department publishes more than 100 papers every year, so there is a vast amount of data on the effectiveness of measuring learning outcomes. In 2009, a study showed that trainees who learned how to perform laparoscopic surgery using a simulator were 50% quicker and twice as safe as those who had not – so these are not marginal gains. In that case, our research was backed by legislation. In Denmark, medical professionals cannot legally perform laparoscopic surgery without coming to CAMES and training on the simulator until they can pass the test. We want this example replicated all over the healthcare industry.”

Despite the frustration, Lars insists most people in healthcare fully support the work organizations like CAMES are doing, and that it is the system that is hard to change. He believes that, although progress might be slow, there are positive signs.

“I am actually optimistic. In the 15 years I’ve been in simulation, we have come a long way. Simulators were once thought of as expensive toys. Now they are taken seriously. In new fields like robotic surgery, evidence-based training has been mandatory from the start because there was no ‘traditional’ barrier to overcome. From the start we were able to demonstrate the value of what we were doing. It starts with the trainees themselves. The more they engage with the simulations and advocate for them, the easier it will be to change the system for the better.”